“Cities across the nation are learning that defunding the police is actually something that moves you into the future.”

*This is part three in a series exploring Arizona’s movements to defund police departments. Read the full series here.

Activists have evoked not only George Floyd, who was killed May 25, but also Dion Johnson, 28, who was shot to death the same day by an Arizona Department of Public Safety trooper who found Johnson asleep in his vehicle near an interstate on-ramp.

“Phoenix police is a problem, they take it too far, they killed Dion Johnson for sleeping in his car,” chanted Phoenix residents gathered outside the City Council chambers in June.

In 2018, Phoenix police officers fired more shots at people than officers in any other major U.S. city, according to an investigation by the The Arizona Republic. The average age of those shot by police was 35, the majority were not white, and a shooting occurred every five days, the Republic reported.

The same day the City Council approved the police budget, it earmarked $3 million toward creation of the Office of Accountability and Transparency for improved civilian oversight of the department’s relationship with the community.

Jamaar Williams, an organizer of Black Lives Matter Phoenix Metro, called the office “the first step in a series of actions” necessary to bring about the reforms Phoenix residents demand.

“Cities across the nation are learning that defunding the police is actually something that moves you into the future and is actually more of a progressive idea than creating civilian oversight,” Williams said. “The city of Phoenix should never have gone this long without civilian oversight.”

RELATED: While The Push to Defund Phoenix Police Grows Stronger, Activists Want Officers Out of Schools

Arizonans want “programs that we can truly benefit from and are going to create safety for us in ways that we’ve needed for a very long time,” Williams said.

Kevin Robinson, who was assistant chief for 13 of his 36 years with Phoenix police, said the oversight board is a smart move toward greater transparency, adding that other police departments need to embrace similar changes.

“I think we’re better than we used to be, but I don’t think we’re as good as we’re going to be,” he said. “There is always room for improvement, you need to think outside of the box and look for other ways to accomplish or to deal with some of these problems that law enforcement is facing.”

In June, Phoenix Police Chief Jeri Williams joined the Police Reform and Racial Justice Working Group, according to KTAR. Williams also has been seen walking alongside protesters who gathered in downtown Phoenix to protest police injustice and praising police officers who took a knee to honor victims of police violence.

“I’m sure the police chief is a great person as an individual, but when she puts on her uniform, when she puts on that badge, that is the entity and the role that we’re critiquing” said Jammar Williams, who is not related to the chief. “Take a knee and be human, great, but I want you to do something about this system, I want you to do something about your job and your function as a public servant and the things that I’m upset about when you do your job out in the streets.”

Complicated history, uncertain future

The model of modern policing has shifted over the past century. Some issues within the system may arise because of the mindset officers develop through training, which has led to police departments becoming overmilitarized and overly aggressive, said William Terrill, an ASU criminology professor and associate dean in the Watts College of Public Service and Community Solutions.

“I think a bigger element here is the mindset of the officer and who is recruiting them and how they’re being socialized into the occupation,” Terril said. “That’s where the police culture comes into play. There’s a reason officers have suspicions, and it’s a very unique occupation.”

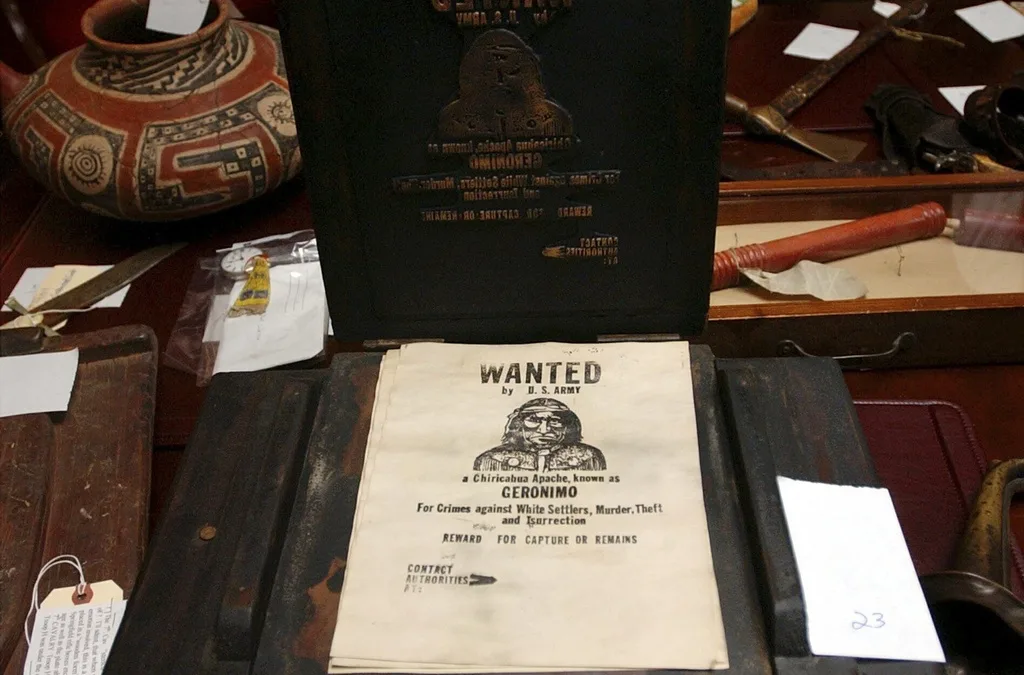

The genesis of modern American policing was born in the South, where police forces developed from groups known as “slave patrols” in 1704, according to the History of Policing in the United States, by researcher Gary Potter of Eastern Kentucky University.

“Slave patrols had three primary functions: (1) to chase down, apprehend, and return to their owners, runaway slaves; (2) to provide a form of organized terror to deter slave revolts; and, (3) to maintain a form of discipline for slave-workers who were subject to summary justice, outside of the law, if they violated any plantation rules,” Potter wrote.

In the 19th century, police forces emerged from private groups that were a response to “disorder.” Eventually, taxes and political influence allowed for the development of professional and bureaucratic policing institutions that equated crime control with social control. Potter wrote that early police departments operated with the goal of controlling “dangerous classes” and had two primary characteristics: “They were notoriously corrupt and flagrantly brutal.”

Terril said the military model of policing continued to develop in the mid-1980s with reform-based policies.

“The notion of that community policing movement was very much what we’re facing now, 40 years later, it was the idea that the police are being too militaristic and we need to be more community based,” Terril said.

The Black Lives Matter movement launched in 2014 after the death of Michael Brown at the hands of police in Ferguson, Missouri. Once controversial, the organization now is widely recognized for advancing human rights.

Americans’ approval of Black Lives Matter has increased by nearly 16 percentage points since 2017, with 53% of Americans in support, 28% opposed and 18% saying they neither support nor oppose the movement, according to a survey in June by Civiqs, an opinion polling company.

Activists say the turmoil over police killings of people of color, global protests in George Floyd’s name and a recognition of the nation’s long history of racial injustice may be a turning point.

Williams, of Black Lives Matter Metro Phoenix, said defunding and disbanding police departments is neither radical nor unrealistic. He describes it as a reasonable solution to the issues of modern policing in America.

“Why are we convincing ourselves that we have no ability to imagine a society where we don’t need police?”

Cronkite News reporter Misha Jones contributed to this series.

Politics

The Civil War raged and fortune-seekers hunted for gold. This era produced Arizona’s abortion ban

Arizona's 1864 code elaborately describes restrictions on duels, ruling any person involved in the fighting of a duel would be imprisoned for one to...

VIDEO: Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs calls 1864 abortion ban ‘absolutely outrageous’ on ‘The View’

@coppercourier Former President Donald Trump and US Senate candidate Kari Lake have both attempted to cover up their support for total abortion bans...

Local News

Trump says he’s pro-worker. His record says otherwise.

During his time on the campaign trail, Donald Trump has sought to refashion his record and image as being a pro-worker candidate—one that wants to...

VIDEO: Hundreds show up in Scottsdale to support reproductive rights

@coppercourier Days after the Arizona Supreme Court ruled to enforce a long-dormant law that bans nearly all abortions, hundreds took part in a...