Graphic via Tania Lili for COURIER

The care the president is likely to receive in the coming days will set him apart from most people who’ve contracted the virus, a disproportionate percentage of whom have been Black, Latino, or low-income.

President Donald Trump announced early Friday morning that he and First Lady Melania Trump have tested positive for COVID-19. They now join more than 7 million other Americans who’ve contracted the novel coronavirus.

The shocking revelation came after Trump spent nine months publicly downplaying the virus, promoting unproven medical treatments, falsely stating that wearing a mask was unnecessary, and insisting the virus would disappear. More than 208,000 Americans have died during that time.

The president’s treatment plan was still being discussed as of Friday, according to the New York Times, but Trump, who is reportedly exhibiting mild symptoms, has already received an infusion of an experimental drug to treat COVID-19, according to a memo from his doctor. The care Trump is likely to receive in the coming days will set him apart from most people who’ve contracted the virus, a disproportionate percentage of whom have been Black, Latino, or low-income.

The suffering among Black communities has been so devastating that one out of 1,020 Black people in the US has died of COVID-19, as of mid-September. The staggering death toll is not only the result of disparities in care and treatment during the pandemic, but the decades-long legacy of structural racism and classism—issues Trump has not had to contend with.

“[Trump] has access to the best science in the world. He has access to the best medical care in the world,” said Dr. Joanna Bisgrove, a family medicine physician in Oregon, Wisconsin. And rightfully so, she added. “Our national security is very dependent on him doing well. We absolutely want him to get better, and so everyone’s going to be right there, everyone’s going to have eyes on him, watching him like a hawk.”

But the comprehensive insurance Trump has and the immediate access to testing and quality care are unique to him and others in similar positions of power. “Not every American has access to this level of care,” Dr. Hilary E. Fairbrother, an emergency medicine physician in Houston, told COURIER.

It’s a reality that has hindered US attempts to contain the virus.

‘We Need Testing to Be Equal and Equitable’

From the early days of the pandemic, it was clear that wealthy people and those with access would fare far better than the average American. When testing was scarce back in March, basketball stars, celebrities, wealthy Americans, and political leaders were able to score tests while most people went without. Due to the lack of a federal testing plan, it took months for some states to begin running the number of tests recommended by experts. Most states still do not meet that criteria.

Six months after the pandemic first emerged, testing shortages still remain a significant issue in some areas of the US, according to a recent report from the Government Accountability Office.

“Officials at seven of eight states we spoke with in July and August 2020 identified ongoing shortages of testing supplies,” the report reads. “For example, officials in one state noted that while they are currently well positioned to meet the demand for [personal protective equipment], testing supplies continue to be in short supply.”

Trump also has access to something many Americans don’t: comprehensive health care. Due to decades of systemic racism and classism—driven by entrenched poverty, education, and wealth gaps—people of color and low-income Americans are particularly likely to go without health insurance. The consequences of this disparity have been devastating during the pandemic.

While coronavirus testing itself is free in most cases, the care affiliated with getting a test often isn’t. Bisgrove offered the example of someone who feels sick, goes to the Emergency Room, and has to meet their insurance plan’s deductible before their insurance company covers additional costs affiliated with the visit.

“Some people’s deductibles can be as high as $4,000, sometimes more. That is devastating,” Dr. Bisgrove said. “The average person in this country does not have enough money saved up to cover a $400 emergency, so suddenly having a $4,000 health bill on your hands is something somebody can’t handle. It’s impossible. So there have been a lot of people that just can’t get care or are afraid to get tested because it’s not just the test, it’s the other bills.”

“You pretend like the most vulnerable aren’t there—not only is it inhumane, but it will come back to bite you.”

There are also significant geographical disparities in the availability of testing, as cities and suburban areas have generally opened many sites, while rural areas have been left behind.

“In Madison and Milwaukee, we have a lot of access to testing and health care,” Dr. Bisgrove said. “We’ve had a horrible time getting testing up into the northern regions of the state, and now we’re seeing—for example in Green Bay, they’re getting overwhelmed completely because they don’t have access.”

Brown County, home to Green Bay, has become one of the nation’s leading hotspots, as cases have surged and hospitalizations have more than doubled in the past two weeks.

RELATED: 90% of Americans Still Vulnerable to COVID-19 Infection, CDC Director Says

The failure to provide widespread testing throughout the country threatens our ability to contain the virus, according to Dr. Bisgrove.

“We would have a much better chance of getting the pandemic under control if testing was equal, equitable, and available and if care was equal, equitable, and available. The core of getting the pandemic under control is that we need testing to be equal and equitable across the country,” she said. “You pretend like the most vulnerable aren’t there—not only is it inhumane, but it will come back to bite you.”

The Legacy of Systemic Racism

It’s not just that the most vulnerable Americans have struggled to consistently access tests. Most people of color have had to continue going to work in person, and a disproportionate number of Black and Latino individuals also work “essential jobs” for low wages. They also get few benefits—such as paid sick leave, which would allow them time to recover from a positive COVID-19 diagnosis without worrying about the financial toll.

Kristin Urquiza, who is Latino and lost her father Mark Urquiza to the virus, has repeatedly spoken out about the consequences of these devastating disparities.

“It’s not because the pandemic disproportionately on its own likes the genetic makeup of Latinos. This is the legacy of systemic downplaying and racism amongst our society rearing its head in the face of a pandemic,” Urquiza told COURIER last month. “These are the people who don’t have the privilege to Netflix and chill. These are the folks who if they don’t go to work, they can’t pay rent and if you can’t pay rent, you’re going to be on the street.”

In contrast, a much higher percentage of white workers have been working remotely from home. In some cases, many wealthy people also fled crowded cities for small towns and rural communities, bringing the virus with them.

Due in part to their struggle to get health insurance and other negative social determinants tied to the legacy of systemic racism and classism, people of color and low-income Americans also suffer from higher rates of many chronic diseases—a leading risk factor for COVID-19.

“Eighty percent of a person’s health is determined by their social outlook: where they are, where they live, where they went to school, whether they’re exposed to pollution, the kind of food they are able to eat, whether their family has stable housing, you name it,” Dr. Bisgrove said. “Genetics are there, but the opportunities you have in life determine your ability to live a healthy life.”

“Even though he is at this point in time where he’s older, he’s had all of these advantages all of his life to help him now.”

Trump, meanwhile, was “born and raised a white, wealthy male,” Dr. Bisgrove said. He is elderly and technically meets the criteria for obesity, she said, but “when you look at social determinants of health, he has [almost] everything going in his favor.”

She noted his upper-class upbringing, steady access to health care, access to the best food and top-class education. “Even though he is at this point in time where he’s older, he’s had all of these advantages all of his life to help him now.”

A Ripple Effect That Would Affect the Most At-Risk Americans

Such disparities have been baked into the US for decades, but they could actually get worse in the coming years because of Trump’s quest to repeal the Affordable Care Act. If the Supreme Court strikes down the 2010 healthcare law, it would leave more than 20 million Americans uninsured and allow insurers to once again discriminate against the up to 133 million Americans living with pre-existing conditions.

“If we have learned anything from this pandemic,” said Dr. Fairbrother, “it is that all Americans need to have access to quality health care. In our current system, Americans gain access to health care through health insurance, so any measure that decreases the number of insured people in the US, worsens the health of those citizens.”

Not only would repealing the ACA exacerbate disparities in access to care, Dr. Bisgrove said, but it could also “undermine the ability to end the pandemic.” The US government has gone all in on developing a vaccine as fast as possible. But to do that effectively requires infrastructure, and in some cases, may require people to have health insurance or pay out of pocket.

“The government bought tons of vaccines to get people vaccinated, but we don’t know if all those are going to work, What they’ve bought so far is not enough to cover everybody—I don’t know that we’re going to be able to buy enough to cover everybody,” Dr. Bisgrove said.

RELATED: Trump Wants to ‘Terminate’ Health Care for Millions During a Pandemic

This means that individuals, doctors’ offices, and insurance companies may have to buy their own vaccines, which could make it more difficult to distribute them widely, efficiently, and equitably.

Overturning the ACA would also create a ripple effect that leads to primary care offices shutting down because their patients lost insurance and could no longer afford care.

“Where do people get vaccinated? Usually their primary care doctor’s office,” Dr. Bisgrove said. “They’re being considered a critical part of the infrastructure to get people vaccinated. If doctors’ offices start closing in mass because of the massive drop off in revenue stream because the Affordable Care Act falls, who’s going to vaccinate?”

Such an outcome would disproportionately affect the most at-risk Americans, including those who are older, people of color, low-income people, those who work frontline jobs, and those who do not have the means to get frequent, quality health care.

But what happens to them also stands to affect the rest of the population. “Unless you’re in a bubble, there’s always the risk of someone getting it,” Dr. Bisgrove said.

This makes equitably distributed testing, treatment, and ultimately, vaccination all the more critical.

“We have to act as a team. We have to act as a country to come together. Everybody needs to be treated equitably,” Dr. Bisgrove said. “If we’re going to get out of this pandemic we need equity, because otherwise we’re going to be sitting in the cycle of the pandemic for far longer than we really deserve to be.”

READ MORE: ‘Blood on Their Hands’: Americans Who Lost Loved Ones to COVID-19 Blast Government Response

Politics

VIDEO: Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes indicts 18 ‘fake electors’

@coppercourier An Arizona grand jury has indicted former President Donald Trump's chief of staff, Mark Meadows, lawyer Rudy Giuliani, and 16...

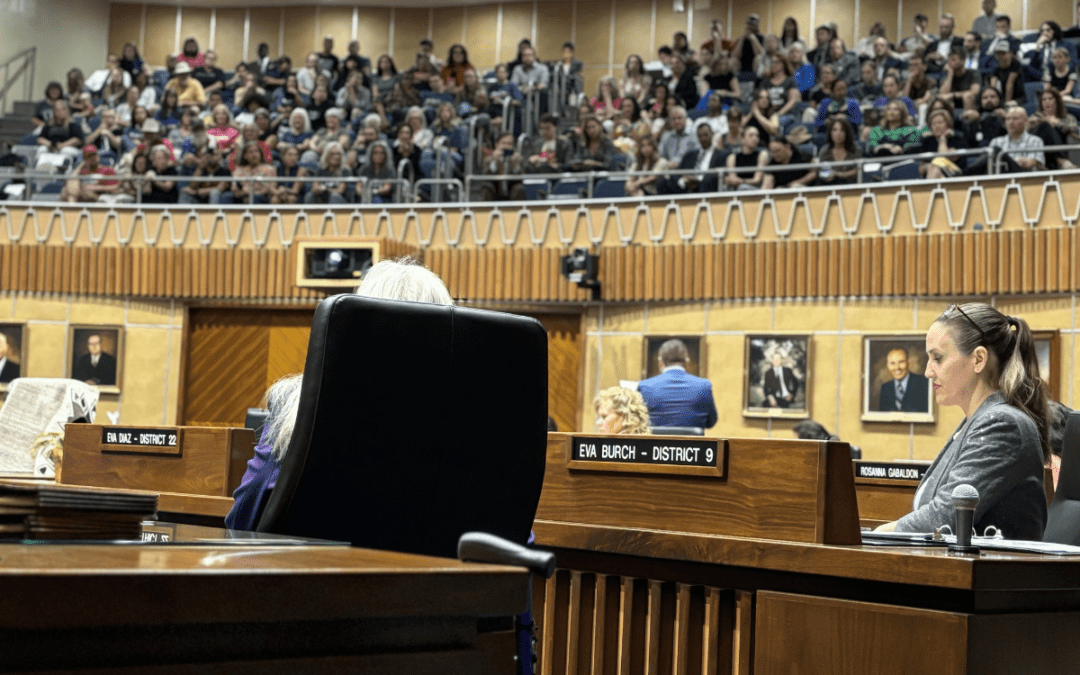

Democrats successfully force vote on repealing 1864 abortion ban, passes House

The Arizona legislature moved forward two bills Wednesday that would repeal the state’s 1864 abortion ban. A bill to repeal the ban has been...

Local News

A new partnership is expanding broadband internet access in rural Arizona

In the state of Arizona, the goal to expand broadband internet access in rural areas has made significant progress with the new public-private...

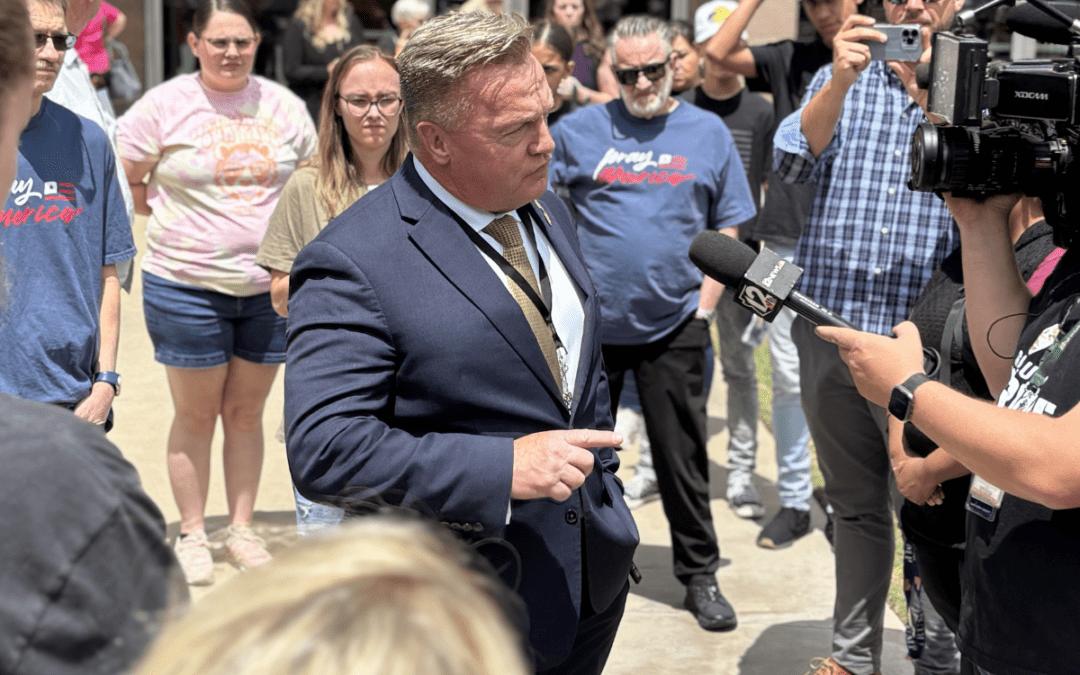

Arizona Sens. Anthony Kern, Jake Hoffman, indicted for fake election scheme

Eighteen individuals involved in a conspiracy to overturn Arizona’s election results in 2020 were indicted by a grand jury Wednesday and charged...