Photo courtesy of subject

Nearly 40 years after he helped break the Phoenix political machine, former Mayor Terry Goddard is hoping to bookend his political career with a “dark money” ballot initiative that he says will make Arizona’s government more representative.

Update: Proposition 211, The Voters Right to Know Act, was approved by voters in November 2022.

Terry Goddard is a stubborn man. The former Phoenix mayor and Arizona attorney general admits as much himself.

Goddard has run for governor as a Democrat twice—in 1990 and 2010—and lost both times. The 74-year-old Navy veteran has also spent the better part of the last three decades working on restoring a historical building in downtown Phoenix, refusing to give up despite the tedious process.

And now, in 2021, the born-and-bred Arizonan has launched his third—and what he hopes is final—effort to limit the influence of money in state politics. Goddard is doing all this while running his own law practice and serving as president of the Central Arizona Project, the state’s single largest renewable water supply, which serves 80% of Arizona’s population and is focused on trying to address the ongoing drought in the West.

Needless to say, he is a busy man. “My wife tells me I’ve got too much on my plate,” Goddard said in an interview.

Looking for the latest Arizona news? Sign up for our FREE daily newsletter.

There’s a method to the madness, though—a set of principles that drive Goddard’s various efforts: His love of Arizona and his deeply held belief that more civic engagement and citizen participation in government will make the state he calls home a better place.

“It has extraordinary scenery and extraordinary people that I think make it absolutely unique in the country and perhaps in the world,” Goddard said.

The one thing he doesn’t love about Arizona? Its politics. The irony of that statement is not lost on Goddard, who volunteered for various campaigns while in college and also hit the campaign trail with his father, Samuel Pearson Goddard Jr., a Democrat who served as governor of Arizona from 1965 to 1967.

Goddard’s first major foray into politics came in 1982, when he led a successful ballot initiative in the City of Phoenix to change how voters elected their city council members. Previously, the council was made up entirely of at-large members, who represented the entire city and were voted on by all citizens who lived in Phoenix.

That system had allowed for the rise of a sort of political machine, known as “Charter Government,” where council seats usually went to candidates who were backed by the city’s wealthiest special interests. Goddard’s initiative, however, created the district system Phoenix uses today, a shift that is credited with providing better representation for the city’s increasingly diverse neighborhoods and making it easier for ordinary residents to run for public office.

The next year, in the first city elections held under the new system, Goddard ran for the only at-large seat left—mayor of Phoenix—and won at the age of 35. During Goddard’s six years in office, he established the Phoenix Futures Forum, a visionary urban planning program that gave city residents the opportunity to share their ideas and help shape the city’s future.

“A lot of the things I’ve worked on as a public official and as a candidate is to try to increase the credibility of public office and the participation by the public and in their decisions, decisions that affect them,” Goddard said.

Nearly 40 years later, he is hoping to bookend his political career with yet another ballot initiative that he believes will make Arizona’s government more representative and increase public confidence in the governing process.

‘Voters’ Right to Know’ Who is Influencing Their Votes

The Voters’ Right to Know Act—which Goddard hopes will appear on the state’s November 2022 ballot—targets the plague of “dark money,” which refers to political spending meant to influence the decisions of voters, where the original source of the money is not disclosed.

“However we try to cut it and dice it, the thing that makes the biggest difference in American politics is the money,” Goddard said. “Dark money means that major contributors can attempt to influence an election through their money, through their advertisements, without having to tell the voters who they are. It allows anonymous manipulation of the political process.”

Goddard’s initiative would take direct aim at that anonymity by requiring organizations that spend more than $50,000 in state races or $25,000 in local races on campaign media to report all original donors who gave more than $5,000 during an election cycle. Currently, organizations can hide who their original donors are by routing their money through a series of intermediaries. Any group found in violation of the rule would face fines up to three times the amount of the donation, according to the initiative.

“We’re trying to establish a voter’s right to know the original source of all money spent trying to influence voter decisions,” Goddard said. “The most important influence in politics is being exercised in a way that the voters aren’t aware of who is doing it—be it corporate or individual—and I think that’s fundamentally toxic for any democracy.”

This anonymity means Arizonans have to make decisions on how to vote without knowing who might be influencing them by promoting particular points of view or advancing misleading narratives via a barrage of TV advertisements, digital ads, and promoted social media posts.

“That is highly frustrating for voters,” Goddard said. “It causes people to lose faith in their own ability to cast a knowledgeable vote and they tend to think that candidates are not really spokesmen for what they’re talking about, for the positions that they’re espousing—that they’re somehow holding allegiance to all these mysterious forces which are not identified. That is profoundly discouraging to an awful lot of people.”

Goddard believes dark money is a major reason so many voters hold such negative views about politics and government. Only 20% of American adults say they trust the government in Washington to “do the right thing” always or most of the time, according to a 2020 survey from the Pew Research Center.

“Right now, there’s a completely justified suspicion that it’s not the public that people are accountable to if they’re elected to public office, it’s somebody else,” he said. “And that somebody else is very often secret corporations and billionaire manipulators.”

‘A Monstrous Effect in Arizona’: How Dark Money Works

While dark money spending is a nationwide problem, it is uniquely corrosive at the state and local level, where lower campaign and media costs make it easy for dark money groups to dominate elections.

And there is arguably no state that has suffered more from dark money than Arizona. According to a 2016 report from The Brennan Center for Justice, dark money spending in state and local elections in Arizona totaled just $35,000 in the 2006 election cycle. But after the Supreme Court banned the federal government from limiting independent political spending by corporations and outside groups in its 2010 decision in Citizens United vs. FEC, that number exploded to more than $10.3 million during the 2014 cycle, a 295-fold increase.

Yes, you read that right. The amount of dark money spent in Arizona’s 2014 elections was 295 times more than in 2006—an increase that far surpassed surges in the other states studied and the 34-fold increase in dark money spending at the federal level over the same period.

The role of dark money in Arizona is so toxic that Chris Herstam, a former Republican majority whip in the Arizona House of Representatives, told the Brennan Center that it was the “most corrupting influence” he had seen during his 33 years in Arizona politics and government. “While dark money gets a lot of national publicity, it is having a monstrous effect in Arizona,” he added.

For a useful case study in how dark money works in practice, it’s worth examining the 2014 elections for the state’s Corporation Commission, which regulates public utilities.

In 2010, the commission began shifting away from industry sources and toward homeowner-generated solar energy. Four years later, dark money forces spent $3.2 million in ads to elect their chosen candidates for the two open seats on the five-member commission. This was “almost 50 times the $67,000 in dark money spent in races for three commission seats in 2012,” according to the Brennan Center’s report. It was long suspected that the groups were funded by the state’s largest utility business, Arizona Public Service (APS), and in 2019, APS finally admitted that it was behind the dark money.

In effect, APS secretly helped elect two candidates who set the prices the company charged its customers. Their effort ultimately backfired due to significant public backlash and increased scrutiny from regulators, but it still highlights the insidious threat of dark money.

Dark money wreaks havoc at the local level, too. Earlier this year, a dark money group tried to trick voters in south and west Phoenix that a progressive Democratic candidate, Yassamin Ansari, was a Trump supporter.

“Don’t let another election get stolen!” the flyer read, alongside a picture of Ansari. “Make Phoenix Great Again!”

The mailer was sent by a mysterious organization called Americans for Progress, which had not registered with the City of Phoenix, in violation of city law. Ansari ultimately won her election, but the incident highlights the dangerous manipulation that dark money allows for.

Today, dark money is funding the conspiracy-fueled, Republican-led “audit” of the 2020 election results in Maricopa County. Goddard warned of the dangers of dark money as conspiracies continue to gain a foothold in US politics, especially on the right.

RELATED: ‘Findings That Should Not Be Trusted’: Report Outlines Flaws With Arizona’s Audit of 2020 Election Results

“I think dark money plays a big role in the right-wing conspiracy promotions,” he said. “Obviously the sponsors of chaos don’t want anyone to know of their involvement, but given the state of the law, there is no way to prove it. The ‘Fraudit’ in Arizona was paid for with secret funds.”

‘I Want to Change It’

Goddard is not alone in his crusade against dark money. Democrats in Congress are also working to address this issue. While Goddard’s effort would tackle dark money in state and local races, the For The People Act, a bill that would require any group spending more than $10,000 on political ads at the national level to disclose all donors who gave $10,000 or more, stalled out in the Senate. Every Senate Republican voted to block the bill, at least temporarily ensuring its demise in the 50-50 Senate.

The legislation is similar but not identical to Goddard’s initiative. “I think it’s the right thing to do,” he said. “Generally it’s the same principle that the original source of the money, be it corporate or individual, needs to be public, that nobody has a right to hide their involvement in political speech.”

In fact, during the last election cycle, outside groups spent nearly $85 million—a chunk of which was dark money—on the Arizona Senate race between Mark Kelly and Martha McSally, which Kelly ultimately won.

Goddard is so concerned about the crisis of dark money that the Voters’ Right to Know Act marks his third attempt to tackle the problem. His first effort, in 2018, was ultimately defeated by lawsuits from dark money groups, while his second try in 2020 stalled out amid the coronavirus pandemic. Those two initiatives were proposed constitutional amendments, but this time around, Goddard has narrowed his focus and is trying to pass a legislative statute which requires fewer signatures and would change the state’s election laws, rather than the state constitution.

Goddard’s initiative will need to obtain 237,645 valid signatures by July 2022 to qualify for the fall ballot. Despite past setbacks, Goddard remains committed to fighting dark money and believes this lack of transparency and knowledge of who donors are is a contributing factor in the “excessively negative” and “excessively not fact-based” political speech that has emerged in recent years and the broader dissatisfaction with politics today.

He does not expect his initiative to solve all the state’s problems involving dark money, but he is confident it would be a positive step in the right direction. Goddard believes that allowing voters to look under the hood of dark money donations and learn why particular organizations or candidates support or oppose specific points of view “will do a lot to increase the credibility of the folks who get in office and the responsibility that they will have to the public after they’re in office.”

He is also optimistic about his odds, pointing to the popularity of recent efforts to pass similar disclosure measures at the city level in Phoenix and Tempe. Those initiatives were supported by more than 85% of voters in each city, though the Tempe measure was later weakened by Arizona Attorney General and US Senate candidate Mark Brnovich.

Goddard also cited a statewide survey conducted by HighGround, an Arizona Public Affairs firm, which found that more than 90% of voters would support his measure to ban dark money spending in Arizona elections.

These figures underscore the reality of dark money: no one likes it or benefits from it except for certain lawmakers and their wealthy benefactors. So like he did in 1982, Goddard is working to undo the entrenched power of the machine and give power back to the people.

“Arizona is the poster child nationally for dark money domination,” Goddard said. “I’m not proud of that. I want to change it.”

Correction: A prior version of this article incorrectly stated that Tucson voters passed a disclosure measure. It was voters in Tempe who supported such an effort. We regret the error.

READ MORE: ‘Truly a Sad Day’: Supreme Court Upholds Arizona Voter Suppression Laws

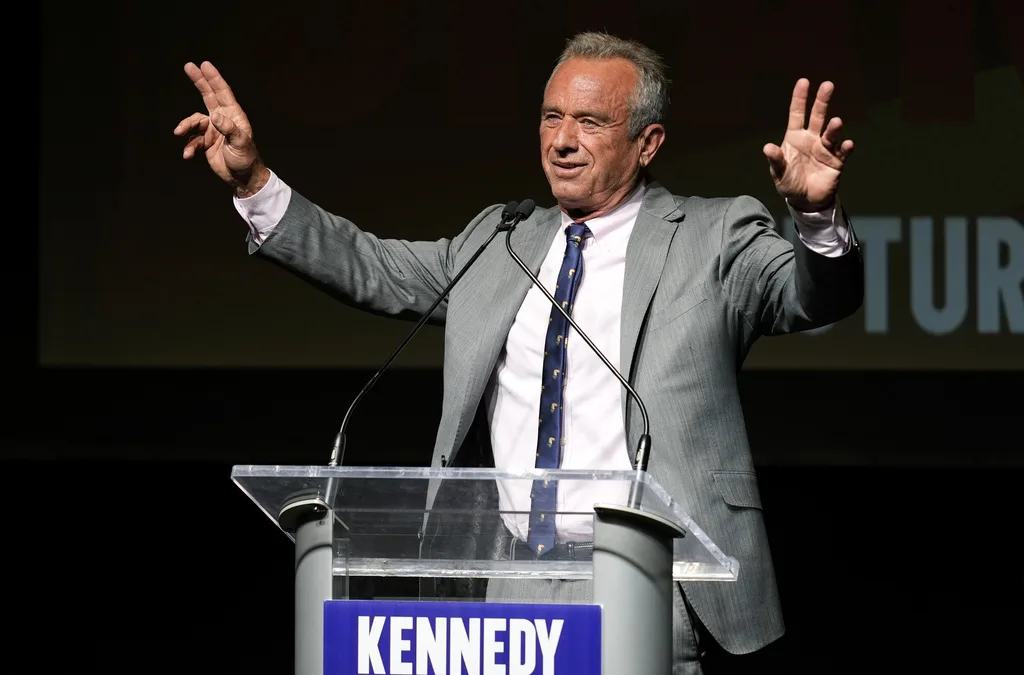

He said what? 10 things to know about RFK Jr.

The Kennedy family has long been considered “Democratic royalty.” But Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.—son of Robert F. Kennedy, who was assassinated while...

Here’s everything you need to know about this month’s Mercury retrograde

Does everything in your life feel a little more chaotic than usual? Or do you feel like misunderstandings are cropping up more frequently than they...

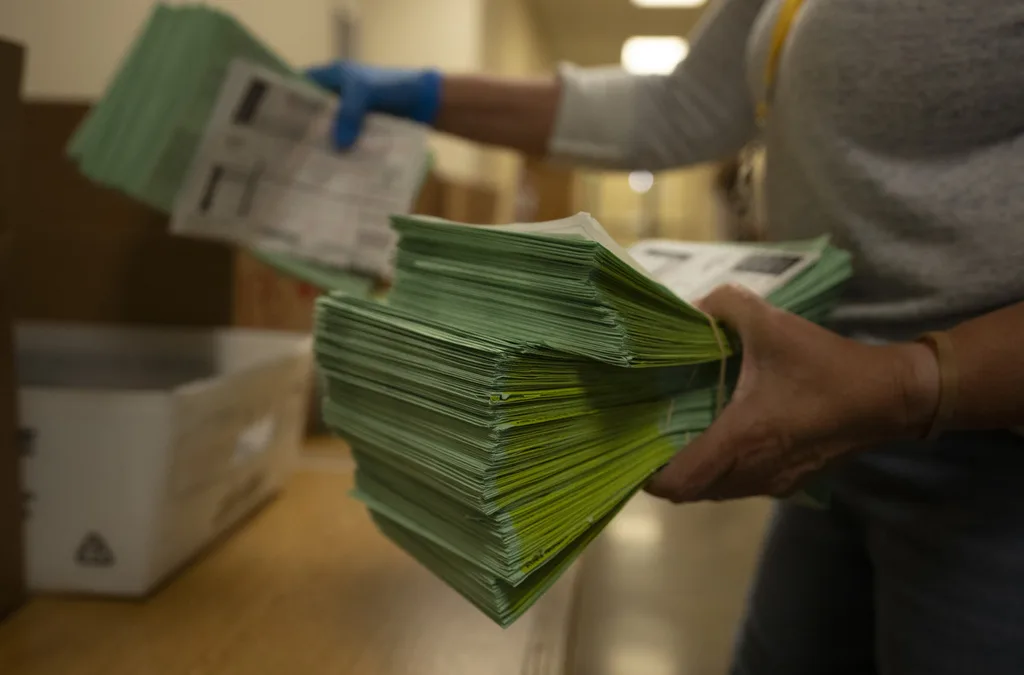

Arizona expects to be back at the center of election attacks. Its officials are going on offense

Republican Richer and Democrat Fontes are taking more aggressive steps than ever to rebuild trust with voters, knock down disinformation, and...

George Santos’ former treasurer running attack ads in Arizona with Dem-sounding PAC name

An unregistered, Republican-run political action committee from Texas with a deceptively Democratic name and ties to disgraced US Rep. George Santos...