PHOENIX, AZ - JANUARY 24: A flag flies outside the Sandra Day O'Connor federal courthouse January 24, 2011 in Phoenix, Arizona. (Photo by Eric Thayer/Getty Images)

In Tucson, more than a dozen unrepresented minors were forced to face an immigration judge and fight removal proceedings.

On Aug. 18, 17 minors appeared in front of Pima County Judge Irene C. Feldman in immigration court. Fourteen of them did not have legal representation.

Lucy, a 3-year-old girl wearing a purple dress and beaded bracelets, was called to the front of the courthouse by the judge. She spoke limited English and did not have legal representation.

A lawyer with the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project (FIRRP), a nonprofit providing legal services, accompanied the child to the stand to provide additional information to the judge regarding her case.

As the judge asked Lucy questions through a Spanish-speaking interpreter about her two stuffed animals, Lucy looked around the packed courthouse with her thumb in her mouth, remaining silent.

She was one of many children without legal counsel.

Judge Feldman asked attorneys with the FIRRP, who were in court representing three of their clients, if they would consider taking on Lucy’s case.

The attorney explained that the organization lost most of their federal funding in March after the Trump administration terminated contracts. As a result, the group is unable to take on new clients.

In the meanwhile, the toddler will have to seek representation elsewhere.

Her case was postponed, and she will have to attend trial on Nov. 24. While FIRRP cannot provide the child legal counsel, they are assisting her in different ways and are hopeful she can obtain sponsorship to prevent her deportation.

The loss of funds has severely impacted the organization’s operations. FIRRP has had dozens of layoffs and has been unable to assist the volume of immigrants it had in previous years. The organization vowed to continue serving the clients they’ve taken on prior to the loss of funds, but for now, cannot assist others despite the Trump administration’s heightened deportation efforts.

The clients FIRRP is currently representing, including Ubaldo, a 17-year-old from Guatemela, Karla, 14, also from Guatemela, and Pablo, 17, from Mexico, were taken on before the loss of funding. The three stood before the judge to request voluntary departure, which allows them to leave the US and return to their home countries.

They each have 120 days to facilitate travel arrangements and reunite with their families.

Voluntary departure can protect immigrants from harsher consequences, including a 10-year ban on reentry. Some migrants choose to leave the country if it means they have more control over how and when they leave, along with allowing for the potential to return.

Other times, the legal process can be so exhausting and confusing for minors that they volunteer to leave and return to their home countries rather than being stuck in detention for months on end.

The children are often placed under the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) after being apprehended by immigration authorities while trying to cross the border, or later referred after coming to the attention of immigration authorities at some point after crossing the border.

ORR contracts with different organizations to provide shelter for minors during detainment, which lasts until their case is resolved or until they are reunited with a sponsor in the US. Children without a valid sponsor can remain in ORR detention until they turn 18 or until a sponsor is found.

The judge asked the three children if they understood they had legal options to consider, including applying for asylum, protection under the Convention Against Torture, or Special Immigrant Juvenile status. They all indicated they understood but still are opting to return to their home countries.

Minors defending themselves

Fourteen minors had to face the judge and request more time to seek legal counsel.

For Sergio, a 15-year-old from Honduras, who entered the US through Texas in January, finding legal counsel has been difficult despite the judge offering him time during his last court hearing. When the judge asked why he hadn’t obtained a lawyer, Sergio said he had been looking but was unsuccessful.

Sergio said he was afraid to return to Honduras, prompting Megan McLean, assistant chief counsel for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), to give him an asylum packet to complete in hopes of avoiding removal.

The judge told the boy through an interpreter, “It’s like homework from school. It’s a project you can do to build your immigration case.”

His next court hearing was scheduled for December to give him enough time to find legal counsel.

It can be difficult for children to obtain representation for several reasons, including high costs, limited access while detained, and general confusion about navigating the legal process.

Francisco, a 16-year-old boy from Guatemala, was the last minor seen. The judge requested a Kʼicheʼ interpreter to help translate for him. Francisco said he fears returning to his home country and asked for more time to find a lawyer.

Judge Feldman replied, “You told me previously you were looking for an attorney,” before granting him an additional four months to seek legal representation.

A sense of distrust

Other defendants said they have family members in the US, and the judge informed them they might have a chance to stay if they consult with their family members.

Many of these minors were fearful of sharing sensitive information about their family members. When the judge asked Nahomy, a 17-year-old girl in pink bracelets, for the contact information of her father, whom she said is a US citizen, she replied in Spanish, “As of now, I’m not wanting to give my dad’s number.”

When the judge inquired on why, the girl said she did not have the number by memory.

The unwillingness to disclose personal information came up often. Brittany, a 10-year-old girl representing herself, walked to the stand wearing a black bow in her hair and a leopard print skirt. When the judge asked if her mother had legal status in the US, Brittany replied, “I don’t want to answer until I have an attorney.”

The judge set her next trial date to Nov. 24 to give the girl and her 15-year-old brother, Bryan, time to find legal counsel.

Most of the minors indicated a desire to have more time to obtain legal counsel, which the judge granted.

For many of them, if they do not have legal representation by their court dates, set for the end of the year, they will need to represent themselves and try to prove to the US government that they should not be deported.

Arizona Republicans in Congress vote for bill that would make it harder to vote

The SAVE Act would require US citizens to show birth certificates or passports when registering to vote, even though tens of millions of Americans...

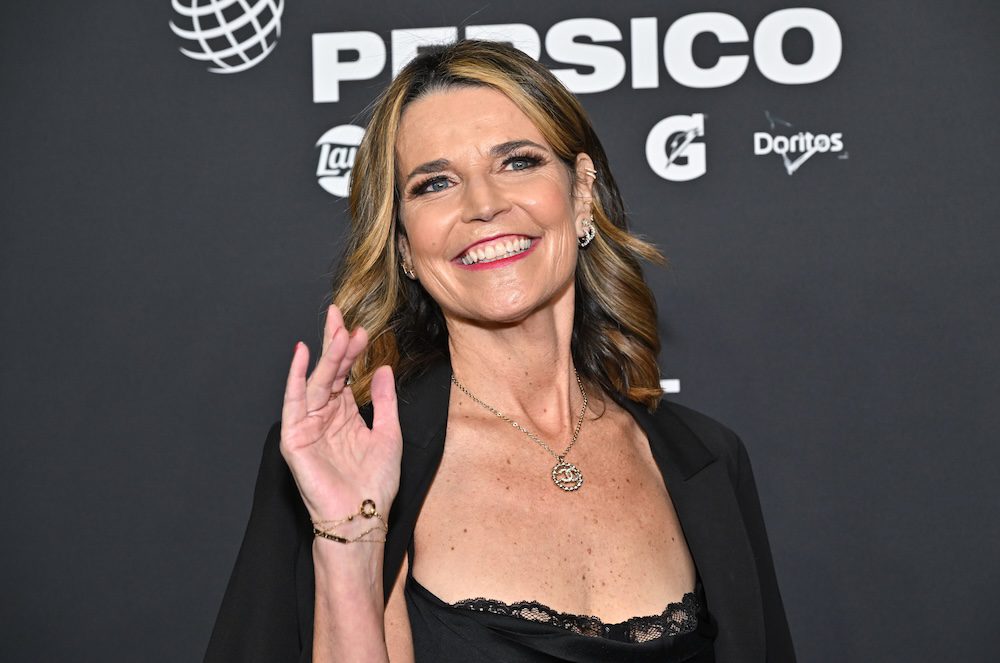

A Walmart backpack may be the biggest clue in Nancy Guthrie’s disappearance

Investigators working on the disappearance of “Today” show host Savannah Guthrie’s mother are consulting with Walmart management to develop leads...

Marana voters may get to decide fate of proposed data centers

The No Desert Data Center Coalition, Worker Power, and other local activists garnered thousands of signatures to let Marana residents decide the...

Arizona sheriff says missing mother of Savannah Guthrie may be victim of a crime

An Arizona sheriff said Monday that “we do in fact have a crime scene” as authorities search for the 84-year-old mother of “Today” show host...