Outside the Tucson immigration court house. Sahara Sajjadi/The Copper Courier

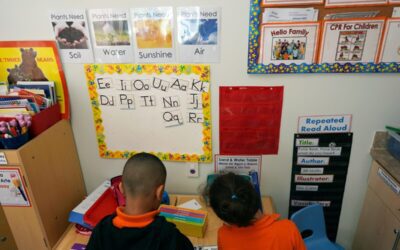

More than a dozen undocumented minors were forced to serve as their own attorneys in front of an immigration judge as the Trump administration ramps up removal proceedings.

Three-year-old Lucy approached the lawyer’s table wearing a multi-colored and floral dress and bright red pants.

The child, barely old enough to talk, was one of 25 immigrant children forced to fight removal efforts by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) at the Pima County immigration courthouse in Tucson on Nov. 24.

Unable to reach the chair on her own, Lucy was lifted into the seat by Ana Islas, a lawyer with the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project (FIRRP), a nonprofit providing legal services to immigrants.

Islas pulled out a brown teddy bear to ease the toddler’s nerves while she faced Judge Irene C. Feldman. Islas is not formally representing Lucy, but provided Feldman with information regarding Lucy’s case due to her age and inability to understand immigration proceedings.

Lucy and the other unaccompanied minors who are fighting removal orders must appear in front of the judge, many without the help of a lawyer, to defend themselves from accusations of illegal entry into the US.

At Lucy’s first hearing in August, an attorney with FIRRP explained that despite a desire to assist the child, the nonprofit lost most of their federal funding in March after the Trump administration terminated contracts. As a result of the funding cuts, the group is unable to take on new clients despite continued demand for their legal services.

Feldman postponed Lucy’s case to November to give her more time to find a lawyer. While she has been unable to do so, Islas informed the judge last week that the shelter Lucy is housed in has made progress in reuniting her with a potential sponsor in the US, and they are optimistic Lucy will perhaps be able to reunite with a family member soon. It is unclear where Lucy’s parents are.

“I hope Lucy gets to safety,” Judge Feldman said before postponing her next hearing to March 2026.

How immigration court works for children

Unaccompanied minors like Lucy flee their home countries for a number of reasons, including to get away from violent crime, gang violence, and economic turmoil— often at the urging of their own parents, according to the National Immigration Forum, an immigration advocacy group.

Children under the age of 18 who arrive in the US without their parents or a guardian and are apprehended by immigration authorities are often placed in the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR).

ORR contracts with different organizations to provide shelter for minors during detention, which lasts until either the case is resolved or until they are reunited with a viable sponsor. Without a sponsor, children can remain in ORR detention until they turn 18.

Often, DHS will issue a Notice to Appear (NTA) against the minors which begins their removal proceedings. An NTA details the reasons why the government believes the children are removable and requires them to attend court regarding their case.

At the initial hearings, the judge is required to share information regarding legal representation, appeal rights, examination of evidence, and more. The judge must also read the allegations and charge of removability in language the defendant can understand, considering their age and other factors.

Judges typically allow young respondents additional time to find legal counsel, and immigrants with legal representation have a higher chance of successfully fighting removal efforts, according to data from the American Immigration Council, a nonprofit focusing on immigration policies.

But hiring an attorney is expensive, and even older children of working age cannot work without a proper work authorization. As a result, many of these children, who are already constrained by living in a shelter, do not have the money to hire an immigration attorney, which can cost anywhere from $1,500 to $15,000, or higher.

“For unaccompanied immigrant children, the barriers are myriad, complex, and nearly insurmountable,” Greer Millard, communications manager for FIRRP, said. “There is virtually no mechanism for a child to find a pro-bono attorney on their own while detained, as they do not have the resources or ability to identify and call attorneys, and are actually limited as to who they can contact.”

As a result, the children often have to fend for themselves, or hope already-stretched thin nonprofits will fill in the gaps.

Others, like Lucy, are too young to understand what’s going on in the first place, which results in the absurd theater of a three-year-old defending themselves in court.

The few children with counsel

Lucy wasn’t the first child to face Judge Feldman on Nov. 24.

The morning began with six kids who had legal representation offered by FIRRP. One by one, they made their way to the lawyer’s table to face the judge regarding removal proceedings.

Three of the children represented by FIRRP—Lucilla, a 15-year old girl from Mexico, and 17-year olds Pablo and Lizen—asked the judge to allow them to voluntarily depart the US, which allows them to leave the country and return to their home countries at the government’s expense.

Lucilla approached the table alongside her lawyer. With a green ribbon tied in her hair, she promptly leaned into the microphone and asked the judge to send her back to Mexico.

“Is that something you want?” Judge Feldman asked regarding removal.

“Si,” Lucilla replied. Yes.

Megan McLean, assistant chief counsel for DHS, granted the request and gave Lucilla and the other two children 120 days to depart the US. Judge Feldman was optimistic they’d make it home soon.

“I hope you get home for Christmas,” Judge Feldman said.

Voluntary departure can protect immigrants from harsher consequences, including a 10-year ban on reentry. Some migrants opt to leave the US rather than fight lengthy removal proceedings if it means they have more control over how and when they leave, along with leaving the door open for a potential return to the US.

Millard explained that undocumented children request voluntary departure for many different reasons, including “exhaustion from languishing in detention, mistreatment or abuse while in government custody, or being separated from loved ones.”

For some, voluntary departure looks more appealing after being stuck in detention for months.

“We see children ask for voluntary departure because the prospect of remaining in shelter detention facilities for an extended period of time seems overwhelming,” Millard said. “Right now, children are facing longer and longer periods of detainment due to increasing obstacles in the reunification process.”

Three other children represented by FIRRP, including 17-year-olds Beshoy and Arafat, and Alejandro, 16, are fighting their removal proceedings and seeking to remain in the US. Their next hearings are scheduled for 2026.

Children without counsel

After hearing from the children with counsel and Lucy, a security guard brought in scores of unrepresented children to begin their fight against removal proceedings.

By the time he arrived in court last week, Nezvid, a 15-year-old from Mexico, had lost hope. When Judge Feldman asked if he had any questions regarding his case, Nezvid promptly replied, in Spanish, “How can I go to Mexico?”

Judge Feldman recommended he weigh the decision a little longer, but Nezvid remained firm in his desire to return home. As a result, Judge Feldman scheduled his next hearing for Dec. 8 to expedite the process of getting him home.

The judge asked Carlos, 15, if he needed more time to find an attorney. Speaking via a Spanish-to-English interpreter, Carlos said, “Yes, because you gave me time last time, and I looked, and it’s not easy to find an attorney.”

“Well, you’ve had time. This is your fifth scheduled hearing,” Judge Feldman said before asking McLean if DHS had any objections to granting the child more time.

With no objection, the judge granted the request and informed Carlos if he did not obtain counsel by his next court hearing, scheduled for Sept. 2026, she would move forward with removal proceedings, and he’d have to represent himself in court.

Elissa, a 13-year old girl from Mexico, informed the judge she had no luck in finding legal representation. After answering a few clarifying questions for the Judge, McLean recommended the girl be removed to Mexico, prompting the judge to ask if she fears returning.

“Si,” yes, she replied. She was given an asylum packet before returning to her seat.

Alida, a 17-year-old girl from Guatemala and Jonathan, another 17-year-old, were also offered asylum packets and instructed to send the application to US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) in Chicago.

Only one child, Xonson, a 17-year-old who is presumed to have run away from the shelter, according to McLean, was ordered removed by Feldman after failing to appear in court multiple times.

Deeper issues

Most of the children were granted extensions to give them additional time to find a lawyer, but a deeper issue persists regardless of the extensions—many of these detained minors do not have the resources to obtain and pay for the legal representation they need to fight removal proceedings.

Without a mechanism to provide these children with support, the chances of them returning to court without legal counsel again is high.

That will result in more dystopian scenes like three-year-old Lucy facing an immigration judge, backed by the full power of the US government and with the ability to determine the course of the child’s life.

After her hearing ended, Lucy cuddled her teddy bear as she walked back from the lawyer’s table and took a seat.

Moments later, the next child was called up to face the judge.

In Tucson, Republican Juan Ciscomani is portrayed as a grinch “who stole healthcare”

Democrats are targeting the Republican Congressman for failing to protect Tucson residents' access to healthcare. Despite verbal commitments to...

Resilience and a Red Ribbon reopening tour in downtown Globe

The fall flooding devastated downtown Globe. Resilience prevails with the reopening of nine businesses. The flooding in Globe wreaked havoc on the...

14 Arizona-based nonprofits to support this holiday season

For many, the end of the year is a season of giving. If you’re searching for organizations that could use your help (whether it be your money, time,...

Want to give back? Check out these coat drives near Phoenix

For the first time since 2010, the poverty rate in America shot up dramatically in 2022, according to data from the Census Bureau. That means more...