The Gault case determined that children have the same rights to due process as adults, including access to a lawyer. However, children are still systemically denied this right.

One day in June 1964, Gerald Gault and a friend made a bad decision. They made an obscene phone call to Ora Cook, Gault’s neighbor. Cook called the police and both boys were arrested and taken to a detention facility in Gila County, Arizona.

The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, establishing the right of children to attorneys, though children’s advocates say legal representation is still uneven.

The juvenile justice system bewildered Gault and his family, according to Supreme Court testimony. Police made no attempts to notify Gault’s parents of his arrest – they only found out later. As Gault’s case made its way through the court, the judge questioned Gault, never with a lawyer present and sometimes without even his parents, and no transcript or recordings were made. The judge sentenced Gault, who was on probation at the time of his arrest, to six years in juvenile detention. Gault’s parents challenged the ruling.

Had Gault been older – at the time of his arrest, he was 15 years old – he would have been automatically guaranteed the right to a lawyer, a right afforded all adults when they are arrested under the 14th Amendment. But because Gault was a child – and children were regarded differently than adults in regards to criminal justice – he was not given a lawyer or any of the other rights he would have received had he been 18.

In re Gault, as the Supreme Court case is known, signified a landmark moment in juvenile justice in the United States: children were officially recognized, for the first time, as having the same legal rights as adults. But over 50 years later, legal experts say the goal of Gault’s case has failed: children across the states are still not provided their right to legal counsel.

A 2017 report from the National Juvenile Defender Center, on the 50th anniversary of the Gault case, found that no state guarantees children access to a lawyer. The children who do get lawyers often don’t get them until after they’ve been interrogated by police, must pay for their own “free” counsel, are encouraged to waive their right to a lawyer, or are denied access to a lawyer after sentencing.

“Even in the cases in which kids are represented there’s wide disparity with regard to the quality and the resources awarded their representation,” said Laura Cohen, director of the Criminal and Youth Justice Clinic at Rutgers University.

According to David Tanenhaus, a professor of history and law at University of Nevada, Las Vegas, the juvenile system was not designed to have the same formality and procedures as the adult criminal system. Experts recognized that adults and children are fundamentally different – adults require punishment for their crimes, while children and adolescents require rehabilitation – and so they established distinct legal systems.

“The logic of the original juvenile court is that you should think about what a child needs – so it was more based on needs than thinking about constitutional rights to due process,” Tanenhaus said.

As a result, the juvenile system was not originally designed to provide youth with a defense attorney. The end result, juvenile defenders say, is a system that is not well-equipped to provide legal help to kids who need it. The rules that had been established to protect kids from the formality and procedures of the adult system failed Gault: he was a youth suddenly facing an adult’s punishment, with no recourse available to defend himself.

The Gault case determined that children have the same rights to due process as adults, including access to a lawyer, as protected by the 14th Amendment. However, children are still systemically denied this right.

“Sometimes, children are put in a position where they have to waive their right to counsel or feel that they have to waive the right to counsel,” said Cohen. “In other situations, the quality of counsel they receive is below what the Constitution requires and certainly not what any of us would want if it were our own child who were appearing before the court.”

According to Cohen, there are numerous roadblocks to change. Some are philosophical, like the longstanding belief that justice system involvement is good for children. Others are financial – many public defender offices are grossly underfunded, with juvenile defenders sometimes working enormous caseloads on impossible schedules.

While Gault did require that youth have access to counsel, it did not require that states establish public defender offices equipped to do so. Because of this, some children — particularly those living in rural areas – are forced to rely on private defense attorneys, according to the 2017 NJDC report.

Instead, overworked public defenders have inadequate time, training or resources to properly handle juvenile cases. This is a problem because cases involving juveniles are a lot more complicated than cases involving adults.

“It takes a lot longer to represent a child,” said Tim Curry, the legal director at NJDC. “I can’t expect to have one meeting with [a child], go through all these complicated legal situations and expect that to be it.”

Curry and Cohen agree that another major reason that changes are slow to develop is the structural racism that is baked into the juvenile justice system. Cohen said that while white children offend at the same rate as non-white children, “children of color are disproportionately arrested, disproportionately charged, disproportionately prosecuted and disproportionately incarcerated.”

Since NJDC’s report, some jurisdictions have been working to improve their public defender offices’ counsel to juveniles. Cohen said that while the case moved the juvenile system in the right direction, the standard established by In re Gault remains far from reality.

“There’s a lot of work that remains to be done,” she said.

This report is part of an investigation into juvenile justice in America produced by the News21 program at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Communications. For the complete Kids Imprisoned project, visit kidsimprisoned.news21.com.

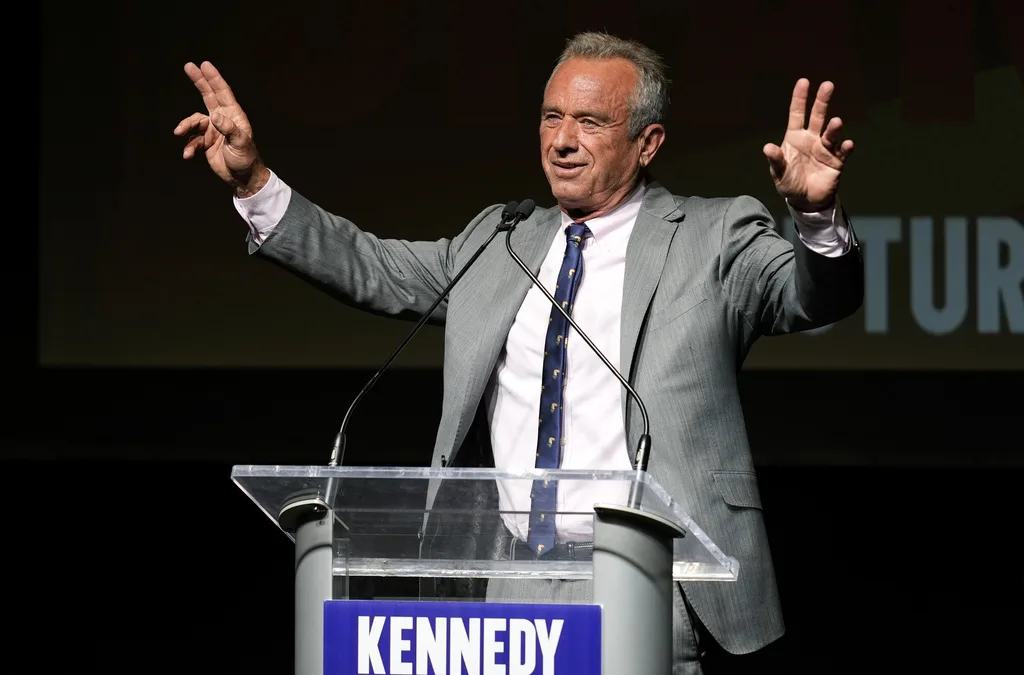

He said what? 10 things to know about RFK Jr.

The Kennedy family has long been considered “Democratic royalty.” But Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.—son of Robert F. Kennedy, who was assassinated while...

Here’s everything you need to know about this month’s Mercury retrograde

Does everything in your life feel a little more chaotic than usual? Or do you feel like misunderstandings are cropping up more frequently than they...

Arizona expects to be back at the center of election attacks. Its officials are going on offense

Republican Richer and Democrat Fontes are taking more aggressive steps than ever to rebuild trust with voters, knock down disinformation, and...

George Santos’ former treasurer running attack ads in Arizona with Dem-sounding PAC name

An unregistered, Republican-run political action committee from Texas with a deceptively Democratic name and ties to disgraced US Rep. George Santos...