After months of silence, conservationists and victims of uranium radiation renew calls for Sen. Martha McSally to support mining ban around Grand Canyon.

A group of tribes and environmental organizations released a statement last week urging Sen. Martha McSally to support legislation to prevent mining companies from digging for uranium near the Grand Canyon.

The National Congress of American Indians and nine other state and national organizations are asking for McSally’s support of the Grand Canyon Centennial Protection Act. The bill, introduced by Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, would set in stone a 20-year ban on uranium mining instituted by the Department of Interior in 2012 after a spike in the ore’s value resulted in more than 10,000 mining claims around the Grand Canyon. It would cover 1 million acres around Grand Canyon National Park.

This past October, a companion bill led by Reps. Raul Grijalva (D-Ariz.) and Tom O’Halleran (D-Ariz.) passed the House 236 – 185 with bipartisan support.

“Protecting the Grand Canyon from deadly uranium mining should be a priority for both of the Grand Canyon state’s senators,” said Taylor McKinnon, a public lands campaigner at the Center for Biological Diversity. “The Grand Canyon region is under new threats from the Trump administration despite the uranium industry’s toxic legacy.”

In addition to the Grand Canyon Centennial Protection Act, Sinema introduced another bill that would establish all of Chiricahua National Monument, a nearly 12,000-acre park near Wilcox, Arizona, as a unit of the National Park Service. Currently, only 86% of the park is under protection by law. McSally co-sponsored the bill.

When Copper Courier reached out to McSally for comment on her decision to support protections for Chiricahua Monument, but not the Grand Canyon, she did not respond for comment.

“This should not be a difficult call for a senator from Arizona to make,” said Amber Reimondo, energy program director for the Grand Canyon Trust. “Arizona is ‘the Grand Canyon State.’ It’s also the home of extensive, deadly uranium mining contamination that, after decades, continues to destroy the lives and health of Arizona residents, particularly on the Navajo Nation.”

But while state lawmakers and fellow conservationists seek to protect the future, the victims of uranium’s toxic legacy still suffer from the wounds of the past.

A lifetime around uranium

William Olague was 18 years old when he moved away from his hometown of Winslow, Arizona, but his doctors have told him the radiation exposure resulting from living downwind of nearby uranium mines and nuclear weapons testing sites will be with him for the rest of his life.

Olague is one of the many northeastern Arizona Downwinders who paid the ultimate price from exposure to nearly 200 nuclear weapons tests conducted by the US government from 1945 to 1962 at a test site in southeastern Nevada. The testing, powered by uranium, occurred across the western US.

He said his exposure to the radiation lasted seven years, but the side effects did not manifest until 2018, nearly 50 years after he left Winslow.

“It just came out of the blue,” Olague said. “I thought I was having some heart issues, so I went to the doctor, and they did a biopsy and said it was multiple myeloma.”

Multiple myeloma is a rare form of cancer, with most people diagnosed in their mid-60s. While doctors have not established a clear cause of multiple myeloma, it is on the Justice Department’s list of compensable diseases for downwinders.

During his time in Winslow, Olague said he never worked at a uranium mine, or really even paid them much attention. When he moved to Las Vegas in 1969, he remembered vividly seeing explosions from the nuclear test site light up the skyline.

“We’d stand out there and watch the bombs go off.”

“I’d hear the sirens go off at night, and because they’d do above-ground testing at night, all the people in the casinos would run outside, and we’d stand out there and watch the bombs go off,” Olague remembered. “And then everyone would applaud, then go back into the casinos and gamble.”

While nuclear explosions could be seen from Las Vegas, the city was safe from the levels of radiation exposure Olague experienced back home. Testing, in that case, had emitted radioactive debris scattered by wind through rural parts of Nevada, southern Utah, and northeastern Arizona.

After the tests ended, a series of class-action lawsuits were filed on behalf of thousands of people who worked in the mines or lived close enough to them and weapons testing sites to be exposed to the radiation. The fallout resulted in ongoing health problems, death, and generational impacts that continue today.

Nearly three decades later, Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, offering compensation to those impacted by mining and nuclear testing. Those who worked in the mines were awarded (and still are) the largest sum, $100,000; those who lived in the affected region were eligible to receive $50,000, as long as they lived downwind of the test site for at least two years, between the years of 1951 and 1958.

Unintended consequences

Born in 1952, Olague is one of more than 23,000 Downwinders who have successfully filed for compensation through the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act since its passing in 1990. Overall, 36,633 claims have been approved, totaling just under $2.4 billion in payouts.

After nearly six months of treatment, Olague’s cancer went into remission. He has been told by doctor’s that environmental exposure to radiation has altered his body on a genetic level, and runs the risk of relapse for the rest of his life.

“It’s a monster, and it’s gonna come back,” he said. And with the price tag on his medication sitting at $531 per daily injection of Alkeran, Olague says the silver lining to his diagnosis was that it happened while he was on Medicare. The $50,000 he received as compensation would only have covered roughly three months of shots.

Executive opposition

The Trump administration has vowed to veto the legislation, claiming that it violates an executive order designed to foster US independence on energy and economic growth. Without any other mining ban extension in place, the companies responsible for 831 active mining claims will have the green light to unearth uranium when the ban lifts in 2022.

However, both claims of energy dependence and economic opportunity from the Trump administration fall flat with regard to mining near the Grand Canyon, according to advocates of the mining ban. A 2018 report from the Energy Information Administration found that the US’ reliance on foreign uranium is at an all-time low. As for financial opportunity, the National Park Service estimates the uranium at the Grand Canyon is worth approximately $40 million, while tourism to the park generated $1.2 billion in 2018 alone.

Although the state’s economy does benefit from the park’s tourism, those who have lived near uranium mining say they are more concerned about the health risks associated with exposure to uranium than any economic impact that may come with it. That includes the rural Arizonans suffering from life-threatening illnesses associated with previous testing, and those who have lost loved ones to those illnesses.

When asked about ending the ban on uranium mining around the Grand Canyon, Olague was immediately against it. He said that while the costs of treatment weren’t a burden for him, it could ruin the lives of those without health care.

“It would be a total disaster,” he said. “My situation was different. Most people, they’ll lose their home, lose their health – you lose everything.”

From little help to none at all

But what little help is offered to alleviate the financial burden Downwinders face is on its way out. The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act was given a sunset date of 2022 – the same year the mining ban is scheduled to be lifted. Any future claims surrounding radiation exposure from uranium bomb testing would not be covered, leaving those suffering to foot the bill.

A bipartisan effort to extend the fund’s expiration date was announced by Arizona House Reps. Paul Gosar and Greg Stanton in late February. The bill would push the deadline to file for compensation to 2027, and would also extend the region of coverage to include Clark and Mohave Counties.

“For too long, residents in lower Mohave County have been left behind in federal efforts to bring justice to Downwinders,” said Stanton. “This bill will ensure that innocent Arizonans affected by our country’s national security decisions will have access to the healthcare treatments and resources they deserve.”

A work in progress

Gosar has introduced legislation to expand the coverage area for several years. His first attempt was a joint effort with former Sen. John McCain, who proposed a companion bill in the Senate. Neither bill was voted on, and Gosar has continued introducing similar legislation every year since.

“Military testing is vital to ensuring our nation is prepared to protect against hostile threats. Unfortunately, this military readiness exposed many Arizonans to cancer-causing carcinogens from atmospheric nuclear tests,” said Gosar.

He added that he remains committed to correcting the injustice committed by the federal government that has adversely impacted the residents of Mohave County.

McSally joined in 2019, co-sponsoring legislation with Sinema that would be inclusive to Mohave and Clark County residents. But her proposal kept the 2022 deadline to file a claim, and was never brought to the Senate floor for a vote.

An uncertain future

Opponents to ending the mining ban have also been voicing their displeasure since the idea was first announced in 2017. Hopi Tribe Vice President Clark Tenakhongva has seen the negative impact of uranium mining firsthand.

“The consequences of mining affect the people and the environment where the digging takes place,” Tenakhongva said at the time. “The contaminants get in the groundwater and travel through the entire region.”

But the wishes of tribal leaders went unheeded by the Mohave County Board of Supervisors, who voted unanimously to disregard the federal ban and expand uranium mining to the land surrounding the Grand Canyon. The board, made up entirely of Republican officials, said the economic benefits outweigh the risks.

Rep. O-Halleran, who supported the House bill to extend the ban indefinitely, criticized the board’s decision.

“I am extremely displeased to see this vote in Mohave County,” he said. “We must ensure that this sacred land is protected for the groups that call it home and all who know it as a spiritual place. I will continue fighting to protect our Canyon from the toxic legacy of uranium mining.”

Overall, a majority of Arizonans oppose expanding uranium mining in the state. But without the passage of either Sinema or Grijalva’s bill, Grand Canyon mining is back on the table in 2022.

Support Our Cause

Thank you for taking the time to read our work. Before you go, we hope you'll consider supporting our values-driven journalism, which has always strived to make clear what's really at stake for Arizonans and our future.

Since day one, our goal here at The Copper Courier has always been to empower people across the state with fact-based news and information. We believe that when people are armed with knowledge about what's happening in their local, state, and federal governments—including who is working on their behalf and who is actively trying to block efforts aimed at improving the daily lives of Arizona families—they will be inspired to become civically engaged.

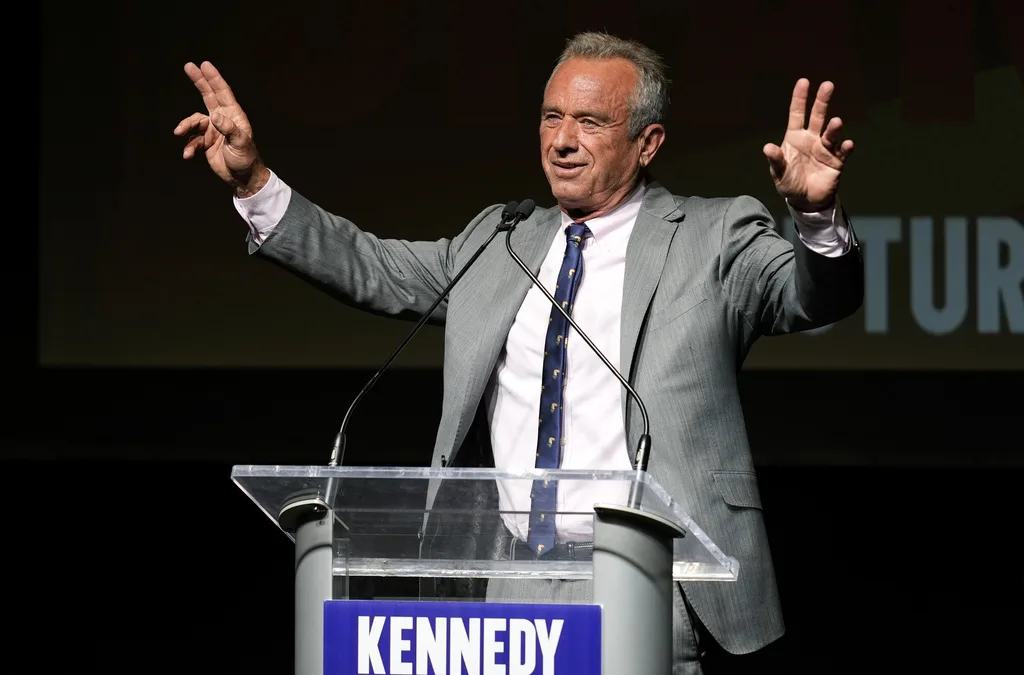

He said what? 10 things to know about RFK Jr.

The Kennedy family has long been considered “Democratic royalty.” But Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.—son of Robert F. Kennedy, who was assassinated while...

Here’s everything you need to know about this month’s Mercury retrograde

Does everything in your life feel a little more chaotic than usual? Or do you feel like misunderstandings are cropping up more frequently than they...

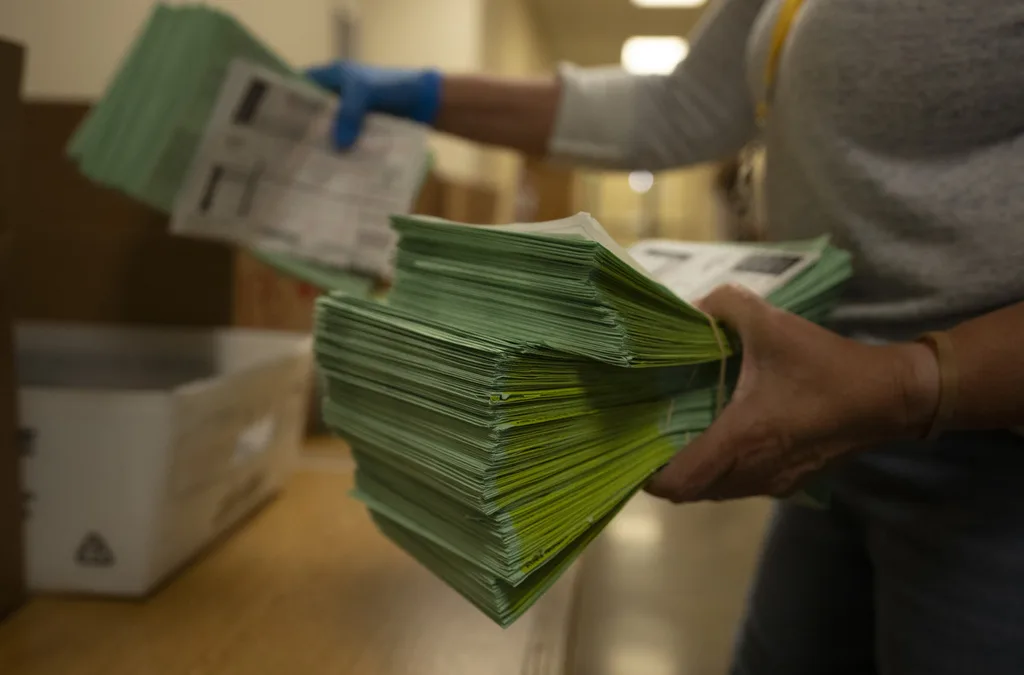

Arizona expects to be back at the center of election attacks. Its officials are going on offense

Republican Richer and Democrat Fontes are taking more aggressive steps than ever to rebuild trust with voters, knock down disinformation, and...

George Santos’ former treasurer running attack ads in Arizona with Dem-sounding PAC name

An unregistered, Republican-run political action committee from Texas with a deceptively Democratic name and ties to disgraced US Rep. George Santos...