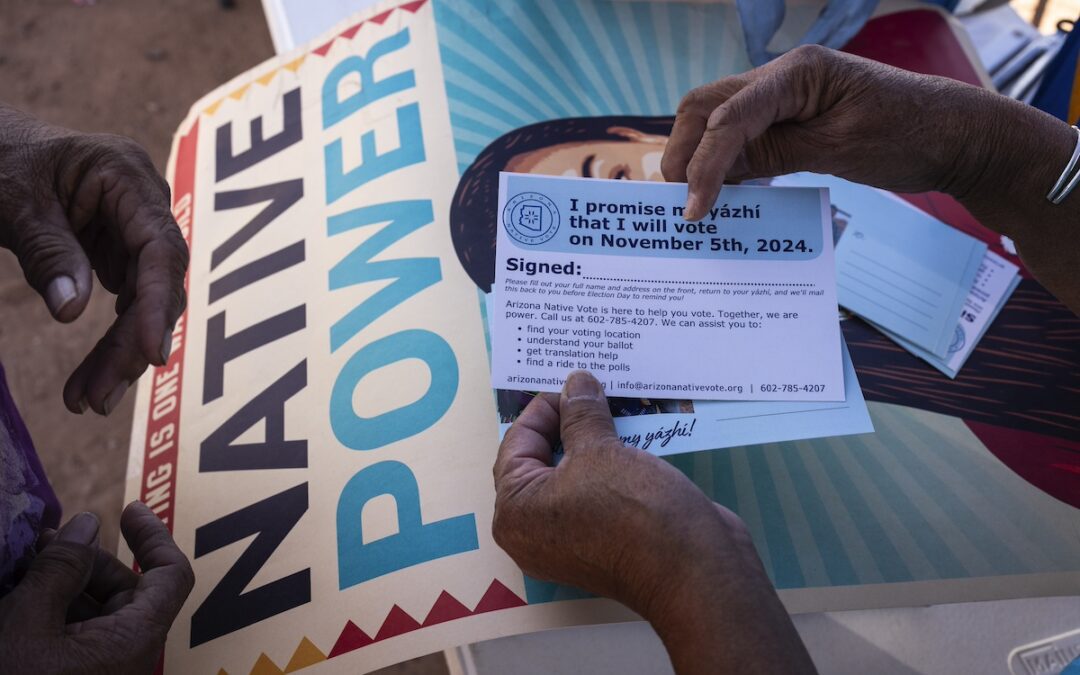

Organizers in Indigenous areas face barriers like historic disenfranchisement and physical distance between would-be voters. In Arizona, one native outreach organization is drawing on the power of its own community members. (Photo courtesy of Arizona Native Vote)

Organizers in Indigenous areas face barriers like historic disenfranchisement and physical distance between would-be voters. In Arizona, one native outreach organization is drawing on the power of its own community members.

Jaynie Parrish understands the power of representation.

During her early work as a political organizer in 2011, she noticed that while voter registration organizations expressed interest in reaching residents of tribal communities, very few organizers were actually connected to the communities they sought to work with.

“We’ve seen so many gaps,” said Parrish, a citizen of the Navajo Nation who grew up in Wind Rock and Kayenta, Arizona. “They’re on their computer in Phoenix and never left Maricopa County, but yet they’re leading a team that’s supposed to work with tribal communities. And it just never made sense.”

In response to those concerns, Parrish founded Arizona Native Vote in early 2023. The nonprofit organization employs Native organizers who connect with community members to build voting power and increase civic engagement across Arizona’s tribal and rural areas. But while the official organization is new, Parrish emphasized, Indigenous leaders have been doing this sort of outreach for decades.

“They’re just not formalized as ‘field director’ or ‘field organizer.’ But there are people who I’ve termed our ‘Election Grandmas and Grandpas,’ Navajo and Hopi and other communities that have been doing this work for generations,” she explained. “They’ve been registering people to vote, fighting for our voting rights. And we get to formalize their role with us through the nonprofit.”

Small margins, longtime disenfranchisement drive Native organizers

In Arizona, which is home to 22 federally recognized tribes representing some 296,000 residents, the Native demographic is decidedly influential. Parrish said Arizona Native Vote aims to register 1,600 new voters in tribal communities during this election cycle—but this relatively small number can mean significant voting sway.

She points to previous Arizona elections where outcomes were determined by a tiny sliver of votes. In 2022, Democrat Kris Mayes defeated Republican Abraham Hamadeh to win the Arizona attorney general seat by a margin of only 208 votes—and the impact of her win on Arizonans’ daily lives has been significant.

Mayes has refused to enforce a Civil War-era abortion ban after the state Supreme Court upheld it, which has since been repealed; cracked down on price-fixing among landlords; and revoked permits for a proposed Saudi Arabia-owned farm that would jeopardize the state’s water supply.

Arizona’s similarly competitive at the presidential level. In 2020, President Joe Biden defeated incumbent Donald Trump in Arizona by a mere 10,457 votes in a state where some 3.4 million ballots were cast.

“A lot of those votes to the deciding factor came from Indian Country. It came from Native communities,” Parrish explained. “It really can make that much of a difference. Make those 1,600—we’re going to find them, be best friends with them, and hopefully they’ll show up and vote with the rest of the team.”

Historical disenfranchisement of Native communities adds another barrier to the work of Arizona Native Vote, Parrish said.

While Indigenous communities were granted citizenship in 1924 under the Snyder Act, many were still prevented from participating in elections because the Constitution left specific voting rights up to individual states. Native suffrage wasn’t granted in Arizona until 1948, though barriers like poll taxes and literacy exams still prevented many Indigenous people from casting votes. Today, Parrish said, the fight for truly equitable access continues.

“We’re fighting for spaces in spaces that weren’t meant for us. We’re trying to find pathways so that we can vote. And there’s people still to this day that don’t want us to vote,” she explained. “They are trying to take away ballot boxes. They are trying to make sure the county offices aren’t funded appropriately. They’re trying to make voter ID more challenging. ‘No, you can’t use your tribal ID. Yes, you can use your tribal ID.’”

Photo courtesy of Arizona Native Vote

‘They’re going to make these policies with or without us’

For many would-be Native voters, Parrish said, highlighting “threads of connection” between the federal government and everyday issues for Indigenous groups is key. Parrish herself didn’t register to vote until she was in her late 20s, despite being involved in her community.

“I think it was because I was still figuring out as a young person, there was no thread for me. I knew there was racism, discrimination, all the crap our tribal communities have endured with the state and the US government,” she said. “I knew all that.”

Despite this knowledge, she said, it took more education and a closer look at history to believe that she and her community members could wield meaningful power through voting.

“It finally took a lot of experiences to thread the needle. Knowing what I knew about our history and how we made changes to that vote, how policies have consequences. And that was all intertwined,” she continued. “And sometimes that’s what a lot of our people need. And anybody, actually, I should say, that they need to see the real life day-to-day consequences.”

Looking back as an adult, Parrish said, she realizes that those “threads” have always been present. She remembers an experience in high school, when she transitioned from schooling on the Navajo reservation to a city-run school. Her non-Native classmates were discussing the copays they’d been charged for annual physical exams.

“I’m like, ‘What is a copay? What’s insurance? What are you talking about?’ I said, ‘We’ve got the Phoenix Indian Medical Center. We just go over there,’” she recalled. “And I’m like, ‘You guys have to pay for your healthcare?’ That’s because of federal policy and our treaty rights that we have health [care]. It may not be the greatest all the time, but we never have to be fearful of, ‘Oh, God, what is that going to cost?’ If I’m sick, we just go to the nearest Indian Medical Center or clinic and we can be seen.”

Parrish also shared the story of one Hopi ‘grandma’ who didn’t register to vote until she reached her 50s, when she encountered a family health issue that couldn’t be adequately dealt with through the local tribal governing body.

“She had to deal with the county and the state, and then eventually through the Indian Health Service that we had, and it was a personal conundrum—but she saw more of the complete picture,” Parrish said. “There was a policy piece with health that came through with her family that the tribe could not cover.”

The woman’s experience gave way to a “thread of connection,” Parrish explained.

“She said, ‘We have to be in these spaces to voice these things. They’re making decisions on our behalf as Hopi people, and we need more of our people to be there and to voice our concerns. They’re going to make these policies with or without us, and we have to be there.’”

Cross-generational ties, rural access strengthen Native outreach

Organizers with Arizona Native Vote dedicate time to everything from home visits to community events in an effort to connect with potential voters, often combining hands-on community aid with civic outreach.

“Sometimes it’s not even talking about voting and elections. It’s being helpful, it’s providing need, mutual assistance,” Parrish said. “It’s being of help, knowing that either the tribal agencies or individuals or groups can call upon us if they need help with certain things.”

Employing Native organizers in their own communities is especially powerful, Parrish said. Organizers connect with community members in a multitude of ways, from sharing a deep understanding of tribal communities’ historical distrust of the federal government to simply taking time to speak with residents who live in rural areas.

“Two hours is a regular drive to go to certain communities,” she explained.

The Navajo Nation comprises over 17 million acres of land across three states.

“And you can’t say things like, ‘go online.’ That only works to a degree, and certain people only have access to that, but you’re not going to get to the grandmas who are good voters, or maybe they haven’t voted in a while, but they’re not going to go online. They’re not going to go on their phone. So you have to deliver news and information in a real way,” Parrish continued.

Photo courtesy of Arizona Native Vote

Reaching young voters is another pillar of the group’s work. Parrish said working with high school students to increase political literacy and encourage civic engagement offers a sense of hope for expanded outreach among future generations of Native voters.

“Our Firekeepers are our matriarchs. And these are like the grandmas I’m talking to that have been doing this for years, and they’re getting older,” she said. “They can’t be lifting their tables and canopies and things around a lot anymore. So the idea is to have this intergenerational work with our young folks, and then our elders that have been doing this work so that they can eventually retire.”

Parrish recognizes that not all would-be Native voters will express enthusiasm about partaking in a system that has so often disenfranchised and directly harmed them, pointing to everything from federal Indian Boarding Schools to devastating termination policies.

But she urges members of her community to take a close look at state and federal policies—many of which have deeply impacted Native communities—to consider where their voting power and influence can make a difference. It’s careful use and navigation of these systems, she said, that create cultural shifts in Native communities and beyond.

“Native voters, we’ve been here a long time. We have a lot of history to pull from that has consequences now,” she said. “Voting is connected to our voice, our power—policies that are going to have consequences on us, whether we like it or not, or whether we shape them or not.”

Arizona Democrats will bypass struggling state party in midterms, with key races on ballot

PHOENIX (AP) — Top Arizona Democrats said Tuesday they will bypass the financially strained state party and its embattled new chairman in next...

Lawsuit centers on power struggle over elections in Maricopa County

PHOENIX (AP) — The top elections official in one of the nation’s most pivotal swing counties is suing the Maricopa County governing board over...

Election official in Arizona’s largest county signals a shift away from combating disinformation

One of the top election officials in Arizona's largest county, which has been roiled in recent years by conspiracy theories and intimidation of...

New study shows voting for Native Americans is harder than ever

OKLAHOMA CITY, Okla. (AP) — A new study has found that systemic barriers to voting on tribal lands contribute to substantial disparities in Native...